Livestock & equine nutrition – what can we learn from each other?

- Home

- Livestock & equine nutrition – what can we learn from each other?

Like many nutritionists, Kayleigh Manthorpe has recently made the transition away from the livestock sector. After 16 years working predominately with pigs, it was time to return to the wonderful world of horses. Since making the switch, and even before this point, it is clear there are many similarities, and of course differences, between species.

Probably the biggest fundamental difference between equine versus livestock nutrition is the end goal. Livestock are generally fed to produce a product for human consumption and thus the production outputs are measures such as: kilograms of meat, number of eggs or litres of milk. As a result, low cost and efficiency are the key drivers. In pig and poultry sectors, the nutritionist generally has 100% control of every element that an animal eats in its lifetime. This is why formulating to exact digestible essential amino acid and net energy requirements is fundamental in pig nutrition, with a lot of research into requirements and very little regard given to total protein level, unless there are health issues or environmental constraints.

The end goal in equine nutrition is very different. Owners are looking for nutritional solutions to maximise health, longevity, performance and good behaviour, all things that are often interlinked and harder to measure outputs.

As equine nutritionists, we usually just have control over the diet component that we are formulating, which is usually only a very small amount of a horse’s daily feed intake. With recommended forage guidelines to feed at least 1.5% per kg of body weight, this makes up the majority of a horse’s daily intake. This is similar to the dairy industry where forage also makes up a large proportion of the total mixed ration (TMR). However, they do more testing on their forages than horse owners do and so the variability of this component is more tightly managed.

Cost of feed and supplements, although clearly a factor, is less of a driver in equine nutrition and owner buying decisions. This is a real luxury that the livestock sectors don’t have as it allows us to tailor the diet to the specific horse, where we think it will bring a benefit rather than trying to make something suitable for a whole shed of pigs or justify the cost in terms of more meat, milk or eggs produced.

A significant factor in formulating diets for livestock today is raw material availability and the environmental impact of the feeds. Within the agricultural sector, many retailers and processers are driving net zero forwards and putting their suppliers under pressure to significantly curb their emissions. Most have set much earlier targets than the governments original proposal of Net Zero by 2050.

The first step of reducing emissions is benchmarking where they are today and so we now have the ability in livestock to calculate the carbon emissions in feed. Some producers have already taken this one step further and have asked their nutritionists to formulate low carbon feeds for their farms.

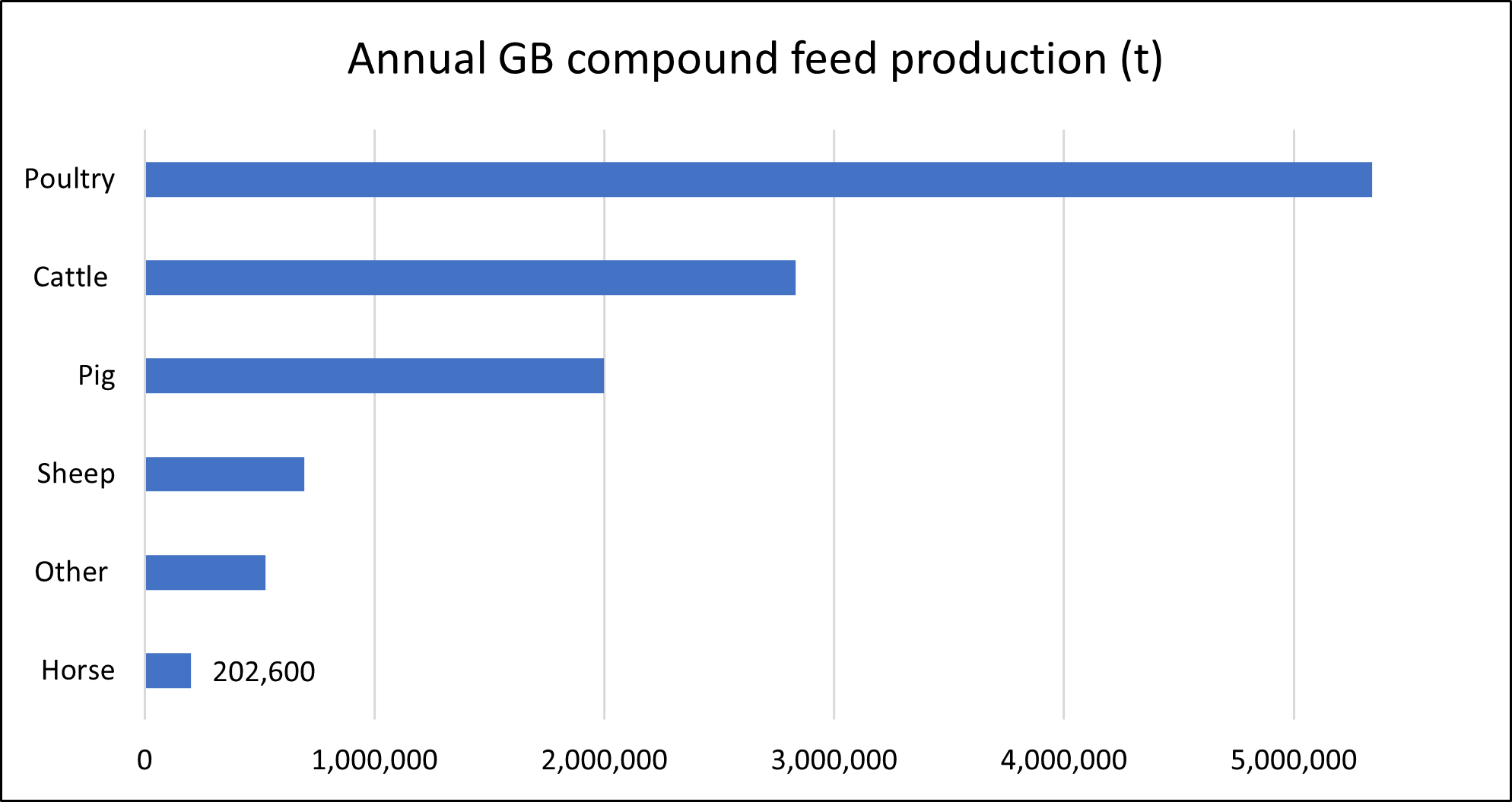

The equine feed industry is still a little way off being able to do this, with the first steps being able to ensure all key ingredients have an emissions value associated to them. The equine sector is very reliant, at least for its major raw materials used in feeds, on what is available and used in other sectors. This is due to the requirements for horse feed being much lower than livestock. In fact, equine feed production accounts for only 2% of the annual British feed production (AHDB, 2022). As a result, we are likely to be more reliant on other sectors leading the way in ingredient selection and sustainability.

Despite the clear differences between the horse’s digestive system and other livestock species, there are also a huge number of similar factors. This means, for feed ingredients at least, it is often possible and fairly common practice to use trial data from livestock studies when considering ingredient selection where equine data is insufficient.

This approach is also very common between livestock species, with most monogastric nutritionists looking to poultry trials to ascertain whether an ingredient will give an affect. The poultry sector are often the trail blazers, partly because new ingredients can be evaluated very quickly due to the shorter lifespan. In addition, well replicated and controlled trials are relatively easy in both poultry and pigs with often dedicated research farms being set up just for this purpose.

One further advantage of using livestock species as nutritional ‘models’ for the horse is that you are often more easily able (with appropriate licences) to look at other parameters, other than just external measurements, such as histology and blood markers. These parameters are often good indicators for equine nutritionists to be able to predict what may happen if we used these ingredients in horse feeds or supplements.

The key drivers for livestock trials are usually improvements in animal productivity, sustainability, or health, either of the animal or the consumer. Because of this, there is an increased incentive from governments and regulatory bodies to make these experiments work, and so there is more funding available to the livestock sector. This is something which the equine industry doesn’t benefit from. As a result, combined with other factors including potential ethical concerns, good horse trials which are well replicated, reliable and have measurable outcomes are few and far between. Frustratingly, all too often, trial data on horses is lacking sufficient controls and replication to be able to draw any reliable conclusions. Instead, researchers and nutritionists often have to relate findings to a physical attribute owners can expect to see or feel in their horses when they use a product. In many ways, equine nutritionists have to be more technical than livestock nutrition colleagues to be able to adapt data from other species and apply them to the horse.

An example of where the high costs and ethical concerns are a limiting factor for equine nutrition is for feed additives. There are only a limited number of nutritional additives which are registered for use in horses. Enzymes, such as phytases, xylanases and proteases, are commonplace in a pig or poultry feed yet there are currently no enzymes registered for use in horses.

Protease enzymes could be interesting if we were able to use them in horses. These enzymes have shown to be beneficial in pig and poultry nutrition. Trials have demonstrated improved protein digestibility, better growth and improved gut health (Tactacan et al. 2016; Park et al. 2020). There has also been recent research into the immune response of weaned pigs fed proteases (Lee et al. 2020) which perhaps could translate into horses to target infection and inflammation.

Xylanases could also be used in horses to enhance and support fibre digestion. Xylanase degrades arabinoxylan, the main NSP found in plant cell walls. Recent research in pigs has exposed a more complicated mode of action for supplemental xylanase than simple viscosity reduction and digestibility improvement (Boontiam et al. 2022). By breaking down the long arabinoxylan chains into shorter oligosaccharides, the substrate available for bacterial growth changes. This changes the microbial community in the gut, increasing VFA concentrations, reducing intestinal pH, and reducing inflammation. This results in large and more resilient villi which promote better nutrient uptake across the gut barrier. Therefore, it would likely translate that in horses where forage quantitiy is reduced or when the microbial population in the hindgut is compromised, the use of xylanase enzymes may be beneficial (Salem et al. 2015).

The limitations in functional feed additives available for use in equine nutrition may be one factor as to why there is a much more open-minded approach to the ingredients considered for use in equine nutrition. Often there is a much higher use of alternative natural supplements such as herbs and botanicals to achieve the same result. One example of this is the use of melon pulp as a source of Superoxide Dismutase, a powerful antioxidant.

One big difference between horses and other species is the size of their stomach. The horse’s stomach is relatively small, making up only 9% of the volume of their total GIT and holding approximately 18L. If you compare this to pigs, whose stomach makes up around 29% of the GIT volume, we can see why the horse is perhaps more prone to digestive issues including gastric ulcers.

Horses are not unique in developing ulcers. Pigs are also susceptible, and this is thought to be largely due to the intensification in pig farming. The exact cause of gastric ulcers in pigs is not fully understood, however it has been associated with particle size and pelleting of diets, feed availability, or other events leading to high stress levels within a herd (Friendship, 2022). It is well recognized that feeding coarsely ground meal or higher fibre diets can reduce the incidence of ulcerations in pigs, although this strategy could result in an impaired feed utilisation with a consequent lower animal productivity and increased environmental load (Millet et al. 2012), making this strategy unpopular in modern intensive pig farming.

Due to their increased susceptibility, better cost flexibility, and open-minded approach, the equine community are perhaps further ahead than other species in finding alternative nutritional solutions to help prevent and reduce the incidence of gastric ulcers.

In the UK and EU, the feed regulatory requirements for both livestock and horses are identical. This means that labelling, quality controls, traceability, analysis and interpretation are easily transferable skills between species. One major difference with horses though is that alongside government regulations, there are also a number of sporting authorities who have their own rules and regulations which the nutritionist must be aware of.

There are a number of prohibited substances laid down by these authorities. Alongside these there is a list of Naturally Occurring Prohibited Substances (NOPS) which are either naturally present within certain ingredients, or occur as a result of inadvertent cross-contamination during processing. Nutritionists and production facilities must manage the risk of feed being contaminated with these prohibited substances within their business.

I am very excited to now be part of the equine sector. Despite the differences, there are a number of similarities between formulating feed for horses and livestock. There is a huge amount of cross over and things that we can learn from each other to apply, with an open mind and a fresh set of eyes, to enable advances in nutrition within our species of choice.

Kayleigh Manthorpe

Equine Nutritionist